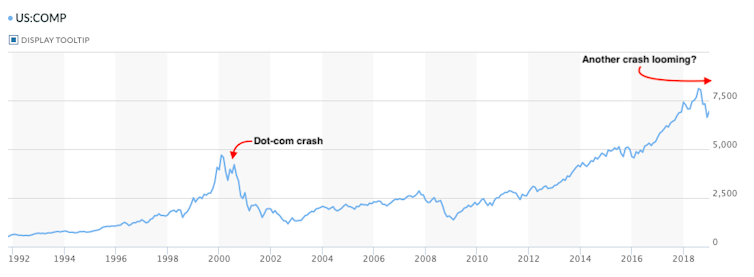

When the dot-com bubble burst in 2000, it sent a significant number of businesses away to Wall. Investment banks encouraged massive investment in Internet ventures by launching initial public offerings (IPOs), allowing investors and entrepreneurs to make huge fortunes by selling shares of their corporations.

Most publicly traded web corporations have done nothing greater than eat vast amounts of investor money and have shown little prospect of turning a profit. Traditional performance metrics were ignored and large spending was seen as a sign of rapid progress.

The money burn was about building the brand and creating network effects – when something increases in value the more people use it. These are the most important drivers of the platform business. For example, in the case of Amazon, the more suppliers there are, the greater the advantages for potential customers and vice versa. Together, this is able to create a foundation for future profits assuming the underlying business case was correct. For the most part this was not the case, and yet almost every idea attracted large amounts of funding.

19 years later, and after a similar “app” boom, investment banks are accelerating IPOs as they anticipate volatile market conditions later in the year. Ride-hailing apps Uber and Lyft, valued by investment banks at $120 billion and $15 billion respectively, are expected to launch in early 2019 to ride out the decline. They each suffer losses – including Uber’s losses to USD 4 billion in 2018 $4.5 billion each loss in 2017. Traditional metrics were ignored and user growth was taken as an indicator of future profitability. However, this requires a huge leap of faith.

Lalala666 via Wikimedia Commons

Uber, like many others, was capable of leverage available funds and raise the funds raised over $22 billion from investors yet. The problem with with the ability to raise funds so easily is that it discourages focus and efficiency. Uber is developing not only a passenger transportation model, but also bike sharing, takeaway food delivery and autonomous vehicles. Most major automotive manufacturers, in addition to Google, are also working on the latter.

Snap Inc, owner of the social media app Snapchat, is also in a difficult situation because it is quickly running out of funds – despite Listings value $24 billion in 2017. Shareholders have no possibility of intervention because only the founding shares have voting rights. LinkedIn still loses money after this Purchase by Microsoft for $26 billion. Twitter has I just made a small profit for the first time after being adopted as the most important channel for announcing US policy by US President Donald Trump.

Investment banks consider that network effects will create economies of scale and create winner-take-all markets that emulate Facebook, Google and Amazon. However, the reality is far from the truth as most of them differ in several essential features.

Two types of applications

Most applications can be divided into two categories. There are those who use content to draw users with the expectation that they may make money from those users – often by selling ads or collecting subscriptions. These include LinkedIn, Twitter, Snapchat, Facebook. There are also those who provide a service or good, resembling Uber, Lyft, Deliveroo, Amazon.

Content apps have discovered that maintaining latest content can be extremely expensive, and monetizing users is difficult when it involves attracting ads and subscriptions. Investor funds are used to develop content in the hope of creating enough users to pay for it and ultimately show a profit. The reality is that users are likely to jump on the next fad before they will make money on it.

Nasdaq

When it involves goods and services, investor funds are used to boost the market through promoting and price subsidies for each suppliers and customers. In effect, they seek to create network effects that are expected to persist after low-price incentives are withdrawn.

However, this is the equivalent of paying suppliers greater than the market rate and then selling to customers at a lower than market rate. In markets with low switching costs, resembling ride-hailing apps and food delivery, users will simply revert to the best offer when incentives are withdrawn.

In the case of Uber, despite its upcoming stock exchange debut, it didn’t withdraw costly incentives as a consequence of a decline in user growth. Economies of scale are also moderately limited, as Uber is checking out by attempting to phase out driver incentives resulted IN Strokes. As a result, the model only works for incentives that investors must fund.

Tero Vesalainen / Shutterstock.com

The big difference with Facebook, Amazon and Google is that they were among the first to build network effects. Uber faces constant competition and fierce resistance around the world, which has led to massive investor-funded battles of attrition. Snapchat has noticed that Instagram and WhatsApp (each owned by Facebook) are waiting for them, making it very difficult for users to compete.

It is only a matter of time before the application bubble bursts. Big tech corporations like Apple AND Facebookthe company’s stock has fallen nearly 40% over the past few weeks, indicating that markets are losing confidence that even established tech corporations will meet their forecasts. This doesn’t bode well for apps that have not been listed yet. When it involves investment markets, history keeps repeating itself.